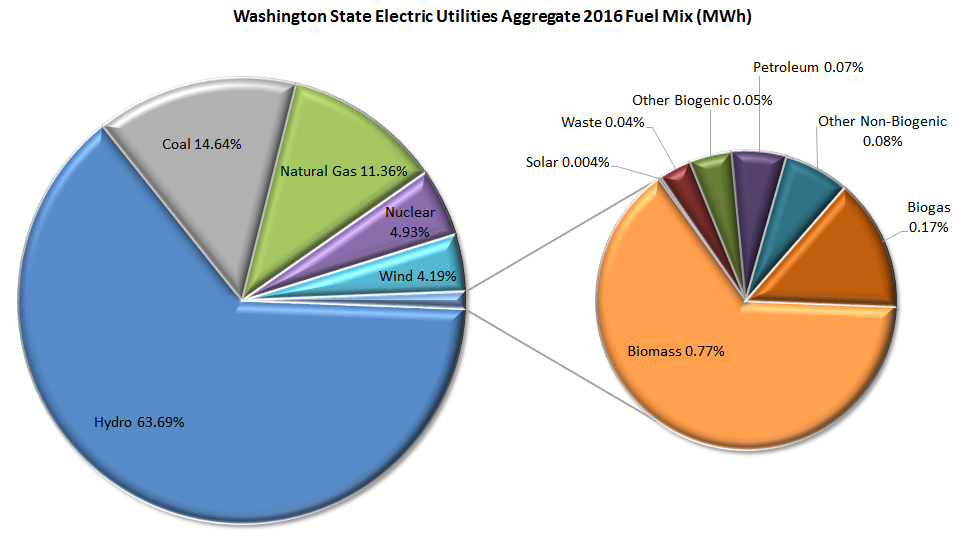

My name is Oluwa Jackson, and I'm living in the Seattle, WA area. We're experiencing a rare blizzard, and local schools and colleges are closed. I'm posting right now because high winds are expected to knock out power this evening, and when that happens that usually means us. I work as a ski instructor, so usually snow is great news - unfortunately the highway to one of our local resorts is closed in both directions due to an uncleared obstacle, and the freeway to our other mountain was so sketchy that I drove part-way to the hill yesterday and then thought better of it and came home (passing a wreck as I did so). What does snow have to do with the water-food-energy nexus, you ask? In this part of the world, a lot. We rely on mountain snowpack to feed our rivers during our yearly summer drought (which has been getting worse in recent years). So, the three feet of snow we got in the mountains over the weekend is great news for our salmon runs as well as our hydroelectric dams. Hydropower is Washington's top source of renewable energy by far, as you can see in the graph below, and supplies most of the state's electricity. We had a late winter this year - less than a month ago you could still see grass poking through the snow - so on the one hand the city was virtually shut down by the weather for a couple of days, but on the other hand we're relieved that snow is finally here.

My undergraduate degree was in Sustainable Practices, making Global Sustainability the perfect Masters program for me. My focuses as an undergrad were on Green Infrastructure (using strategic planting and permeable paving to slow and filter stormwater) and Permaculture (a style of food cultivation that is as far from industrial monoculture as I think it's possible to get, taking a holistic view of the local climate, culture, water and land in order to plan mixed living and farming communities). The Pacific Northwest is a great place to create this style of community, as our river valleys have rich volcanic soil for cultivation, our climate is mild enough for winter crops, and it's easy to find local sources of compost so that chemical fertilizers aren't needed. The drawback is the need for constant weeding of invasive species, which love it here just as much as our cultivars do.

Water, food and energy are overtly intertwined in the Pacific NW. Our salmon runs depend on our rivers, but so does our energy production. Hydroelectric dams have driven some our salmon runs extinct; some large projects such as the Elwha Dam have finally been removed under pressure from local tribes, bring their traditional source of food back to their lands. Agriculture is plentiful here, but agricultural runoff stresses aquatic life through eutrophication. Transportation is a major energy consumer in King County; however contaminant deposition on roadways washes into waterways, and is the top source of pollution in Puget Sound. The Sound and our coastline are an important source of seafood such as oysters and mussels, which are damaged by water pollution. On top of that, our shellfish industry is being threatened by ocean acidification, which prevents shellfish larvae from forming shells. Our oceans are being acidified by CO2, emissions of which are increased by fossil fuel energy generation. Everything is connected: land and sea, mountains and rivers, water and atmosphere; our lives here demonstrate that every day. I hope this class (and this degree) will help me address concerns that affect food, water and energy systems in a way that improves their interdependency and discourages their mutual harm.

No comments:

Post a Comment